If - Else#

In this tutorial we will:

learn about the Python

if elsestatementslearn how to load a volume of blocks into the world from a file

and how to save a volume of blocks to a file

learn how to place buttons or levers in the world and have them call Python code when activated

Logical Operators and Boolean#

Here we will introduce a new type called a Boolean. A Boolean is a value that can only be either True or False.

I can create boolean variables like this:

b1 = True

b2 = False

Python supports the logical operators that you are familiar with from maths. These operators make comparisons between numbers and return True or False (so return a Boolean). e.g. try this in iPython:

In [6]: a = 4

In [7]: b = 6

In [8]: a > b

Out[8]: False

Common logical operators are:

a > b (a is greater than b)

a < b (a is less than b)

a == b (a is equal to b)

a != b (a is not equal to b)

a >= b (a is greater than or equal to b)

a <= b (a is less than or equal to b)

You can also assign the result of a logical operator to a variable. Try this in iPython (reusing values of a and b you assigned a moment ago):

In [9]: b1 = a < b

In [10]: b1

Out[10]: True

Above we compared a and b and assigned the result to b1. The value of b1 is True because a is less than b.

It is important to remember the difference between = and ==. The

= operator is used to assign a value to a variable. The == operator is

used to compare two values. In written maths we do not have this distinction,

but it helps Python to be clear about the meaning of a statement.

Code Branching#

Up to this point we have always executed all the lines of code we have

written in the order they appear in the program. The for loop does allow

us to repeat sections of code. It is also very useful to have more than

one branch of code to execute. To achieve this is we use

if else.

This is reasonably easy to understand as it reads like an English sentence.

Consider this simple function and see if you can work out what it does:

def age_test(my_birth_year, your_birth_year):

if my_birth_year > your_birth_year:

print("You are older than me")

else:

print("I am older than you")

Lets try this with my birth date is 1964 and yours is 2012:

In [12]: age_test(1964, 2012)

I am older than you

There is a bug in our code at the moment. What if the birth years are the same? Then the program can’t tell which one is older without knowing the month and day of each birthday.

We could write the function like this:

def age_test(my_birth_year, your_birth_year):

if my_birth_year == your_birth_year:

print("We have the same birth year!")

elif my_birth_year > your_birth_year:

print("You are older than me")

else:

print("I am older than you")

In this function we first check for the same year. Then we use elif. This

is short for “else if”. So if the years are not the same then it does the

second check for “if my_birth_year > your_birth_year”.

Gate with Working Portcullis#

Now lets use what we have learnt to make a working gate for our village. The following video is a demo of what we will make in this section:

Gateway with Portcullis Demo

The shape of the gate itself is going to be loaded in from a file that I will provide. You will be free to edit the gate to look how you would like it and then save it back over the original file (see Saving Blocks to a File).

The following commands need to be executed in a bash shell. They will

create a folder called blocks and download my sample gate.json file

into that folder

cd $HOME/my_world

mkdir blocks

cd blocks

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/gilesknap/mciwb/main/blocks/gate.json

For the moment we don’t need to look inside the gate.json file. Just know that you can save and load a volume of blocks in the world to and from a file. (Later when we learn about Python Lists we will look inside these files).

Let’s jump right in and make the gate and then go back to explain what we have

done. Create a new module in your buildings package and name it gate.py.

Here is a reminder of how to do that using your bash prompt:

cd $HOME/my_world

code buildings/gate.py

Paste this code into gate.py and save it.

"""

Define a castle gateway with portcullis

"""

from time import sleep

from mciwb.imports import Direction, FillMode, Item, Switch, Vec3, get_client, get_world

def portcullis(position, close, width=4, height=6):

"""

Open and close a portcullis

"""

if close:

steps = range(height, 0, -1)

item = Item.ACACIA_FENCE

else:

steps = range(1, height)

item = Item.AIR

c = get_client()

for step in steps:

start = position + Direction.UP * (step - 1)

stop = start + Direction.EAST * width

c.fill(start, stop, item, mode=FillMode.REPLACE)

sleep(0.5)

def make_gate(position=None):

"""

Create a castle gate with working portcullis

"""

position = position or Vec3(x=623, y=73, z=-1660)

def open_close(switch):

portcullis(position, switch.powered)

gate_pos = position + Direction.SOUTH + Direction.WEST * 2

get_world().load("blocks/gate.json", gate_pos)

Switch(gate_pos, Item.LEVER, open_close, name="portcullis")

def disable_gate():

Switch.remove_named("portcullis")

Note that the build_gate function has a default value for position. I

chose this as a likely entrance point to the village (we will add a

drawbridge later!). If you want to change this you can pass a different

position to the make_gate function. For help in choosing position coordinates

see Discovering the Coordinates of a Block.

To make the gate type this in iPython:

from buildings.gate import make_gate

make_gate()

This should place the gate in the world. Try out the lever and watch the portcullis open and close.

How it Works#

Make_gate#

The first thing that the make_gate function does is define another function

called open_close. This function will be called when the lever is activated.

By defining open_close inside of make_gate we are able to use

the variable position which is needed when moving the

portcullis. (If you want to understand more about this see Variable Scope)

This code always creates a gate facing north. position represents the

bottom WEST corner of the portcullis.

Because we want the stone gate to surround the portcullis we define the position of the South West corner of the gate as a couple of steps to the WEST (left if you are looking North) and one step SOUTH (back if you are looking North).

Next we load in the file we downloaded earlier. This uses the world function

load. In order to get the world object inside of a module we use

the get_world(). Because we need world only once I did not bother to

assign it to a variable, see the equivalent approaches below.

# using a variable to do world.load()

w = get_world()

w.load("gate.json")

# A shortcut to do the same thing

get_world().load("gate.json")

When loading blocks into the world with world.load the position always

specifies the bottom left SOUTH WEST corner of the blocks. Thus if you

face North and choose a block in front of you the loaded object will

extend away from you and to your right.

The final step in make_gate is to create a Switch object, we pass it the

position and the Item type (we use a lever here). The final parameter is the

function to call when the lever is activated.

Open_close#

The open_close function is the callback function that the Switch object

will call when it detects a change in the state of the lever. Switch

callback functions are always passed the Switch object that triggered them.

The Switch object’s most important property is powered which is a boolean

that is True if the lever is currently on and False if it is off.

Therefore this callback will always call the portcullis function and pass it

the original position value that we gave to make_gate plus a boolean

to say if the lever is on or off.

Portcullis#

The portcullis function is called when the lever is activated. It

takes a position and a boolean to say if the lever is on or off.

It also takes a width and height for the portcullis, but we use the default values for these as they match the size of our stone gate.

The first thing we do is use if else to change the function’s behavior

based on the boolean called close. When open_close calls portcullis

it passes the powered state of the lever in as the close parameter.

Thus if the lever is powered then we close the portcullis and if the lever is not powered then we open the portcullis.

How does the opening and closing get represented in the world? We have a for

loop that sets one row of blocks of the portcullis at each iteration, after

each iteration it pauses for half a second. The sleep function from the

built-in module called time is used to provide the pause, note the

import of this function at the top of the file.

The if statement chooses some values for variables used by the for loop

as follows:

Closing:

we set the rows of blocks to

Item.ACACIA_FENCEstarting at the top and working down.

Opening:

we set the rows of blocks to

Item.AIRstarting at the bottom and working up.

Note

The range function we have used so far always counts from zero

upwards. When closing the portcullis

we want to start at the top and work down.

To do this we add additional parameters to the range function.

See

this description

for details of the parameters for range.

The code range(height, 0, -1) creates a range that starts at height

and goes in steps of -1 until before it reaches zero.

Saving Blocks to a File#

The world object also has a save function and you can use it to save a

volume of blocks to a file. Then you can reload those blocks in a new

location at a later date.

To demonstrate this lets build something in Minecraft and save it to a file, then reload it in a new location.

The steps are as follows:

Build something you would like to Save, my example in the video is giant a table.

use the selection sign to select the volume of blocks you want to save: - first select one corner e.g. bottom south west - then select the opposite corner e.g. top north east

in iPython type:

world.save("blocks/table.json")Now select the block where you want to load a copy: - select where you want the SOUTH WEST corner to be

in iPython type:

world.load("blocks/table.json")

For a demo of this feature see the video below.

Save and Load Blocks Volumes

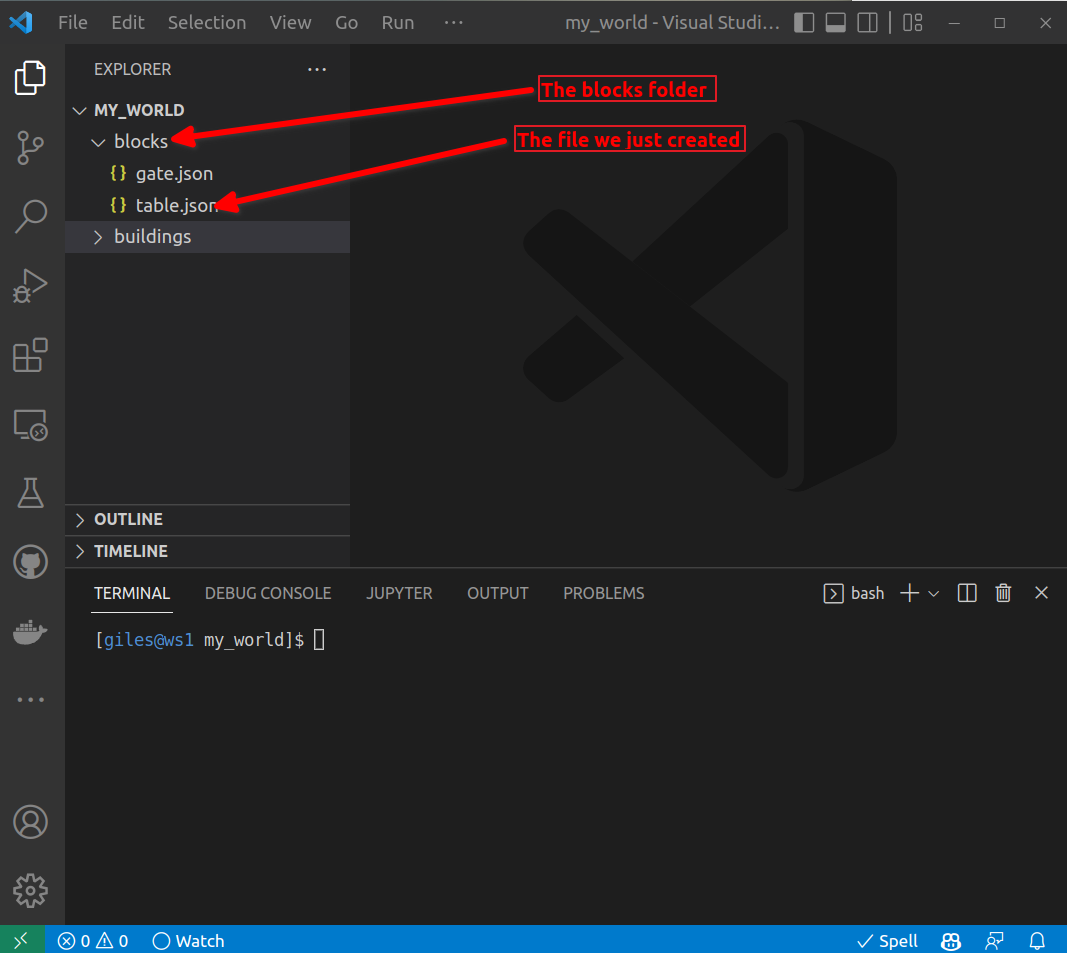

By the way, files that you create with code can be inspected using the vscode

explorer. In the image below you can see the table.json file that we

created in the above steps. To see this

you would need to click on the blocks folder to expand it.

Viewing files in the VSCode explorer#